Are your students struggling to move beyond memorization for their AP exams? It’s a common frustration for dedicated teachers who are teaching AP courses: you know your students are capable of deep analysis, but the pressure to cover content often leaves them stuck on the surface. You’re not just teaching facts; you’re trying to build analytical thinkers and help them master critical thinking, but bridging that gap can feel overwhelming. With Magna Education, that changes. We’ve helped thousands of students master the critical thinking skills essential for AP success. In fact, Magna students have 3X higher odds of scoring a 5 and 2X higher odds of scoring a 4+ on AP Exams. This guide offers a proven framework, not to add more to your plate, but to transform how you teach, making critical thinking the core of your classroom and unlocking your students’ full potential.

Confronting the Critical Thinking Gap in the Classroom

Ever get that feeling you’re under pressure to churn out analytical thinkers, but the daily grind keeps pulling you back to memorization and recall? You are definitely not alone. It’s a common struggle: curriculum standards call for higher-order thinking, but classroom reality often defaults to just getting through the material.

This isn’t just a hunch; the data backs it up. Research has shown that in more than half of all classroom observations, learning was stuck at the lowest cognitive levels—remembering and understanding.

Worse yet, less than one-sixth of classrooms were found to be actively building those crucial higher-order thinking skills. This gap hits students from lower-income backgrounds the hardest, creating an uneven playing field. You can dig into the specifics of these educational disparities in this detailed report.

This guide is designed to give you a practical framework for weaving critical thinking into your daily instruction. Think of it not as one more thing to do, but as a different way of doing what you already do. At Magna Education, we’re focused on making that shift easier and more effective.

Magna students have 3X higher odds of scoring a 5 and 2X higher odds of scoring a 4+ on AP Exams.

We’ve learned a lot from helping thousands of students, and we want to share a more direct path to cultivating the analytical skills they need for AP success and whatever comes next. Let’s get started on making critical thinking the beating heart of your classroom.

How to Master Critical Thinking in Practice

Before we can teach critical thinking, we have to agree on what it actually looks like in a student’s work. It’s so much more than just being “smart” or getting good grades. It’s a specific set of active, observable skills that we can identify, teach, and assess.

Thinking critically isn’t a single lightbulb moment; it’s a process with distinct stages. Students first have to break down information (analysis), then judge its credibility and value (evaluation), and finally, draw well-supported conclusions (inference). These aren’t just education buzzwords—they’re the gears turning behind a powerful AP essay or a sound lab report.

Our goal is to pull back the curtain on this process. Once we establish a clear vocabulary and can spot these skills in action, we can start designing lessons that intentionally target them.

From Vague Ideas to Observable Skills

Let’s ground this in the real world. A student analyzing a political cartoon for bias in an AP U.S. History DBQ is using the same core skill as a student analyzing a data set for outliers in an AP Chemistry lab.

In both cases, they’re dissecting a whole into its parts to understand its meaning, relationships, and structure. The context is different, but the cognitive work is the same. When you can spot that skill—or see that it’s missing—your feedback becomes laser-focused and infinitely more helpful.

Critical thinking is not an innate talent but a disciplined process of actively and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and evaluating information. It’s a skill that must be deliberately cultivated.

To make this concrete, the table below breaks down the core components of critical thinking. Think of it as a diagnostic tool, outlining each skill with question stems you can use tomorrow, ‘look-fors’ to spot in student work, and common pitfalls you can help them correct.

A Practical Toolkit for Identifying Critical Thinking

This framework provides a shared language for what rigorous thinking really means. Use it to guide your Socratic seminars, review written assignments, and sharpen the questions you ask in class. It’s about building a classroom culture where these skills are explicitly named, valued, and practiced.

This table breaks down the key facets of critical thinking, providing teachers with actionable question stems, observable student behaviors (‘Look-Fors’), and common mistakes to watch for across different subjects.

Core Critical Thinking Skills and Classroom Indicators

| Core Skill | Description & Key Questions | Student ‘Look-Fors’ | Common Pitfall to Address |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis | Breaking down information into its component parts to explore relationships. Questions: What are the key parts of this argument? How does this piece of evidence relate to the main claim? What patterns or trends do you see? | Identifies unstated assumptions. Differentiates between fact and opinion. Accurately summarizes the main points of a complex text or data set. | Surface-Level Summarizing: The student simply restates information without dissecting its structure, bias, or underlying meaning. They tell you what it says, not how or why it says it. |

| Evaluation | Judging the credibility, relevance, and significance of information or sources. Questions: Is this source reliable? Why? What are the limitations of this data? Which piece of evidence is most compelling? | Questions the credibility of sources. Recognizes bias in an argument or data presentation. Assesses the strengths and weaknesses of a position. | Accepting Information at Face Value: The student treats all sources as equally valid without questioning the author’s purpose, methodology, or potential biases. |

| Inference | Drawing reasonable conclusions based on evidence and logical reasoning. Questions: What can you conclude from this evidence? What are the implications of this finding? What is the most likely outcome based on this data? | Creates logical connections between different pieces of information. Develops a well-reasoned conclusion that is supported by evidence. Avoids making logical fallacies. | Jumping to Conclusions: The student makes a claim that goes far beyond what the evidence can support, often relying on personal opinion or a single, weak piece of data instead of a logical chain of reasoning. |

With a clear framework like this, you’re no longer just hoping students will “think harder.” You can now point to specific skills, model them explicitly, and create activities that give students the focused practice they need. This foundation is the first step in intentionally designing lessons that build true analytical mastery.

Designing Lessons That Build Analytical Skills

Critical thinking isn’t something students just absorb through osmosis. We can’t simply lecture on the curriculum and cross our fingers, hoping they develop analytical skills on their own. That’s a recipe for surface-level learning. The real key is to intentionally design lessons that embed analysis, evaluation, and argumentation directly into the learning process.

This is about transforming standard topics into compelling challenges. Forget asking students to just memorize the causes of the Cold War. Instead, throw them into a simulation where they have to advise President Truman using conflicting intelligence reports. The focus immediately shifts from passively consuming facts to actively constructing knowledge.

From Activities to Analytical Exercises

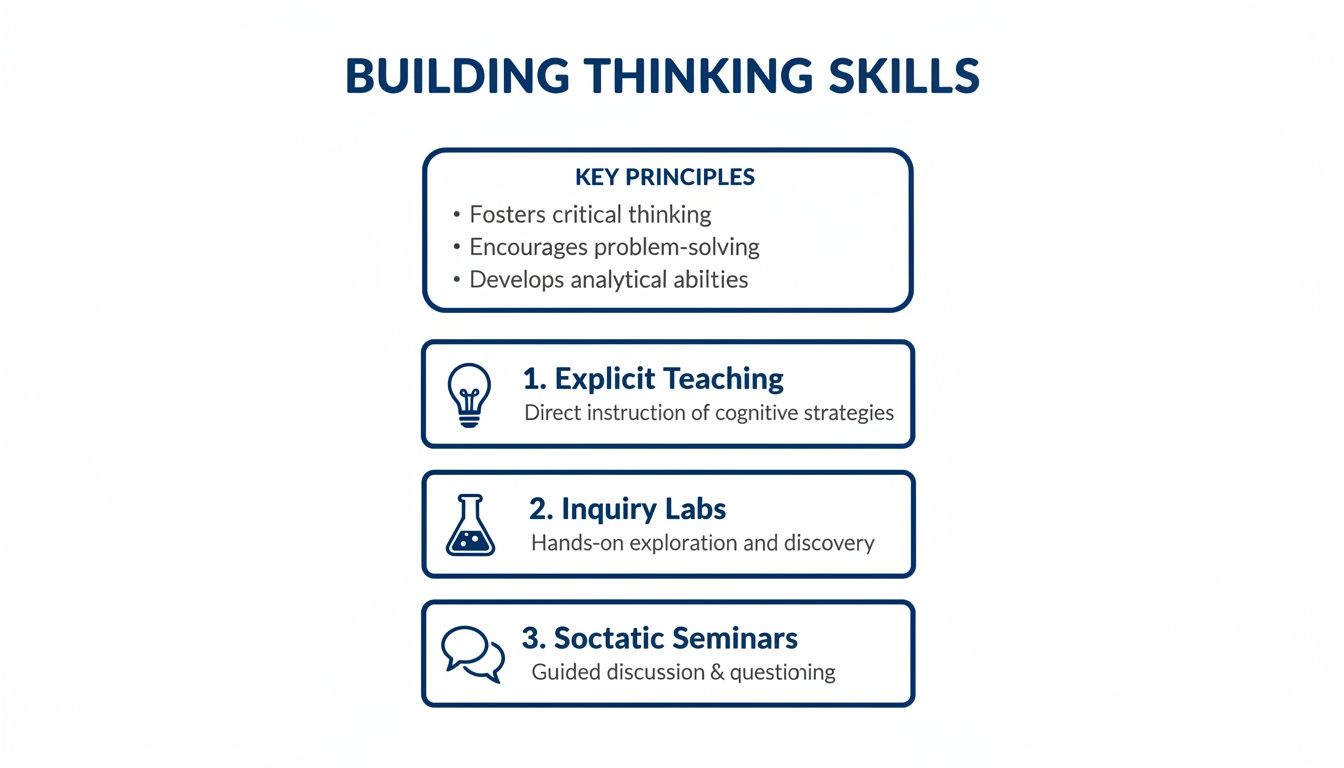

The lessons that really stick are the ones that force students to grapple with ambiguity, weigh evidence, and defend their conclusions. Two of the most powerful ways to do this are with Socratic seminars and inquiry-based learning. These aren’t just one-off activities; they are instructional models that put analytical work right at the center of your classroom.

A Socratic seminar, for instance, is far from a casual chat. It’s a structured dialogue where students absolutely must analyze a text, come up with interpretive questions, and then build on or challenge their peers’ arguments using hard textual evidence.

Likewise, an inquiry-based lab is a world away from “cookbook” experiments where students just follow steps to a known outcome. It starts with a question, a puzzle. It’s on them to design their own procedures, collect and analyze the data, and draw conclusions based on what they actually found.

The goal here is to create a classroom where the “right answer” is less important than the process of arriving at a well-reasoned conclusion. This intellectual struggle is where genuine analytical muscle is built.

Practical Lesson Blueprints for AP Courses

So, what does this actually look like in an AP classroom? It’s all about reframing the content you already teach into a problem that needs solving or an argument that needs building.

Here are a few ways to get started:

- AP U.S. History: Ditch the lecture on the New Deal. Instead, give students a folder of primary sources—a political cartoon, an excerpt from a fireside chat, unemployment data, and a Supreme Court opinion. Their task? Construct an evidence-based argument evaluating the effectiveness of the New Deal. This is a perfect mirror of the Document-Based Question (DBQ) and forces them to synthesize conflicting information.

- AP Biology: Teaching cellular respiration? Present students with data from an experiment measuring CO2 output in yeast under different conditions (like varying sugar types or temperatures). Their job isn’t just to graph the data, but to design a follow-up experiment that tests a new hypothesis they generate from the initial results.

- AP Macroeconomics: Don’t just have students memorize the definitions of fiscal and monetary policy—stage a debate. Assign student groups to represent different economic schools of thought (Keynesian vs. Monetarist, for example) and have them propose solutions to a current economic problem, like inflation, using real data from the Federal Reserve.

These kinds of approaches are fundamental for building the skills needed on exam day. For a deeper dive into preparing for the test, check out our guide on how to ace your AP exams with effective study strategies.

Don’t Forget Explicit Instruction

While inquiry and debate are incredibly powerful, they work best when paired with explicit instruction. You can’t just throw students into a complex task and hope they figure it out. Scaffolding and directly teaching analytical skills are absolutely essential.

Recent studies back this up. Research shows that explicit pedagogical methods are crucial for developing critical thinking, especially when you bring digital tools into the mix. Intentional, systematic teaching—where you guide students through structured processes of analysis and argumentation—has been found to significantly boost academic performance and strengthen cognitive skills.

What does that look like? You might start a lesson by modeling how to analyze a primary source for bias, giving students a checklist or a thinking routine before they tackle it themselves. Or you could use a framework like “Claim, Evidence, Reasoning” (CER) to help them structure their scientific arguments. The inquiry provides the engaging context, while the explicit instruction provides the cognitive tools they need to succeed. This balanced approach ensures all students have a path toward developing the sophisticated analytical skills they need for AP success and beyond.

Assessing Critical Thinking Without Drowning in Grading

You’ve designed a brilliant lesson that pushes students to analyze, evaluate, and create. They’re engaged, they’re debating, and they’re thinking. Now for the hard part: how do you actually measure that growth without creating a mountain of grading that eats up your entire weekend?

Let’s be honest, assessing critical thinking can feel vague and overwhelming. Unlike a multiple-choice quiz, you can’t just mark a complex historical argument right or wrong. The good news is, effective assessment doesn’t have to mean drowning in essays.

By using a mix of smart formative and summative strategies, and embracing the right technology, you can get a clear picture of your students’ skills, provide meaningful feedback, and get your time back. It’s all about working smarter to measure what truly matters.

Moving Beyond the Red Pen with Formative Checks

Formative assessment is your secret weapon for teaching critical thinking. These are the low-stakes, in-the-moment checks that tell you what students are getting right now, letting you pivot your instruction on the fly. Best of all, they give you invaluable data without adding to your grading pile.

Instead of just collecting another stack of papers, try weaving in quick activities that make student thinking visible.

- Complex Exit Tickets: Go beyond “What did you learn today?” and ask an analytical question. Something like, “Based on today’s documents, what’s one potential bias in the author’s argument and why?” This forces a quick moment of evaluation.

- Think-Pair-Share with a Twist: After students discuss a challenging question with a partner, ask them not just for their answer, but to explain their partner’s reasoning. This sharpens both listening and analysis skills.

- Flawed Example Analysis: Give students a weak argument or a conclusion based on faulty data. Their job is to spot the logical fallacy or misinterpretation. It’s a fantastic way to see if they can apply evaluation skills in a practical context.

These quick checks give you a snapshot of student understanding, helping you catch common misconceptions before they take root.

Creating Rubrics That Actually Clarify Thinking

For those bigger assignments—the essays, the research projects—a well-designed rubric is non-negotiable. A great rubric does more than just speed up grading; it demystifies what “good thinking” actually looks like for your students. It translates abstract skills into concrete, observable actions.

Forget generic categories like “Analysis” or “Use of Evidence.” Get specific and break down the skills into measurable components.

This visual really gets at the core of it—strategies like explicit teaching and Socratic seminars are the vehicles, and a clear rubric is the roadmap.

For an AP History DBQ, a strong rubric might include criteria like:

- Argumentation: “Develops a clear, complex thesis that addresses all parts of the prompt.”

- Evidence Evaluation: “Analyzes the source’s point of view, purpose, or context for at least three documents.”

- Synthesis: “Connects the argument to a broader historical context or a different time period.”

A clear rubric transforms grading from a subjective chore into an objective coaching opportunity. It gives students a roadmap for improvement and gives you a consistent standard for evaluation.

When students know exactly what you’re looking for, they’re much more likely to deliver. This clarity makes your feedback more actionable and the whole grading process more efficient and fair.

Leveraging AI for Deeper Insight and Faster Feedback

So, you have the formative checks and the solid rubrics. But grading complex, open-ended responses—like the free-response questions (FRQs) that are the heart of AP exams—is still incredibly time-consuming. This is where technology can become a genuine game-changer.

AI-powered platforms have made huge strides in this area. While traditional methods have their place, they often struggle with providing immediate, scalable, and deeply analytical feedback on complex thinking. AI tools can help bridge that gap.

Traditional vs AI-Powered Assessment of Critical Thinking

| Assessment Aspect | Traditional Methods | AI-Powered Approach (Magna) |

|---|---|---|

| Feedback Speed | Slow; students wait days or weeks for graded essays, delaying the learning cycle. | Instant; students receive immediate, rubric-aligned feedback upon submission. |

| Scalability | Difficult to scale; providing deep feedback to 150+ students is unsustainable for one teacher. | Highly scalable; every student gets personalized feedback on every submission. |

| Objectivity | Can be subjective; prone to grader fatigue and unintentional bias. | Consistent & Objective; AI applies the same rubric criteria to every response, every time. |

| Data Insights | Limited; identifying class-wide trends requires manual tracking and analysis. | Rich & Actionable; automatically identifies common misconceptions and skill gaps. |

| Student Practice | Limited to assignments a teacher can physically grade. | High volume practice; students can work on FRQs as often as they need to build mastery. |

The potential here is huge, especially for AP-level work. A platform like Magna Education is designed specifically to tackle this challenge. Instead of you spending hours reading every single response, the AI can provide instant, detailed feedback on a student’s analytical skills. It doesn’t just check for keywords; it analyzes the structure, logic, and evidence use in their argument.

This allows you to assess critical thinking at scale. Imagine every student getting targeted advice on the strength of their evidence or the clarity of their thesis just moments after submitting their work. You gain rich, real-time data on class-wide skill gaps, freeing you up to focus on targeted reteaching and small-group support. This approach marries the rigor of authentic assessment with the efficiency of modern technology, making it possible to teach and measure critical thinking without the burnout.

Overcoming Common Hurdles in Your Classroom

Turning your classroom into a hub for critical thinking is an exciting goal, but let’s be real—it’s rarely a straight line from A to B. Anytime we introduce a new way of teaching, we’re bound to hit a few bumps in the road. You might run into student resistance, wrestle with differentiating for a wide range of skill levels, or just feel the constant squeeze of the clock.

These hurdles are completely normal. They don’t have to throw you off course. The trick is to anticipate them and have a few strategies in your back pocket. It’s all about being realistic and strategic, not perfect.

The real goal is to create a classroom culture where taking an intellectual risk is celebrated, and mistakes are just part of the learning process. Let’s break down some of the most common challenges and how to handle them.

Addressing Student Resistance

“This is too hard!” or “Can’t you just tell us the answer?” Sound familiar? If so, you’ve encountered student resistance. It’s not surprising—after years of being rewarded for finding the one “right” answer, the ambiguity that comes with genuine critical thinking can feel uncomfortable. This isn’t defiance; it’s a natural reaction to a major cognitive shift.

Your first move is to acknowledge their discomfort and reframe what you’re asking them to do. Make it clear that the “struggle” is precisely where the real learning kicks in.

To ease them into it, start with highly structured activities that have clear scaffolding. Think sentence starters for building an argument, graphic organizers for breaking down a text, or a simple checklist for evaluating a source. These tools act as a safety net while they build the confidence to tackle more open-ended problems.

Building a thinking classroom means shifting the focus from performance to process. Celebrate thoughtful questions and well-reasoned attempts, even if they don’t lead to the correct answer. This shows students that their intellectual effort is what truly matters.

Differentiating for a Spectrum of Thinkers

In any given class, you’ll have students all over the map. Some will jump into a complex analysis without hesitation, while others might still be working to move beyond simple summarization. Differentiating your instruction is the only way to meet every student where they are.

This doesn’t mean you need to create 30 different lesson plans. Instead, focus on flexible strategies that offer multiple entry points and varying levels of depth.

- Tiered Questioning: During a class discussion, plan your questions to build in complexity. Start with basic recall to get everyone on the same page, then gradually move up to questions that require analysis, evaluation, or synthesis.

- Choice Boards: Give students a menu of tasks that all target the same core skill but at different levels. A student needing more support could analyze a single primary source with a guided worksheet, while another might be ready to compare three conflicting sources to construct an original argument.

- Flexible Grouping: Mix it up. Sometimes pairing students with similar skill levels is perfect for targeted instruction. Other times, creating mixed groups allows for peer modeling and some powerful collaborative problem-solving.

This kind of flexibility ensures you’re scaffolding for those who need it while still pushing your more advanced students to stretch their analytical muscles.

Tackling the Time Crunch

This might be the biggest one. We all feel the pressure of having to cover a mountain of content with not nearly enough time. It’s easy to see critical thinking as an “extra” we can’t afford, but that’s a misconception.

The most effective teachers don’t teach content then do a critical thinking activity. They use the activity to teach the content. A debate over economic policy isn’t just an exercise in argumentation; it’s how students learn the nuances of AP Macroeconomics. Analyzing primary documents isn’t an add-on; it’s the best way to actually learn AP U.S. History.

Of course, this integrated approach takes some thoughtful planning. For more ideas on making the most of your instructional time, check out our guide on effective time management for AP students—many of the principles apply just as well to teachers.

The challenge of underdeveloped thinking skills isn’t just something we see in our classrooms; it’s a global issue. A massive OECD study of 120,000 higher education students found that a staggering 20% performed at the lowest level of critical thinking. These aren’t just numbers; they’re a call to action for intentional K-12 instruction. You can learn more about these critical thinking findings to see just how vital this work is.

By tackling these hurdles head-on, you’re doing more than just prepping kids for a test. You’re giving them the essential tools for lifelong learning and engaged citizenship.

FAQ: How Magna Boosts AP Exam Performance

How does Magna help students improve their critical thinking for AP exams?

Magna’s AI-powered platform is designed to target the specific critical thinking skills required for AP success. Instead of simple memorization drills, students engage with thousands of AP-aligned free-response questions (FRQs). The AI provides instant, detailed feedback on their analysis, argumentation, and use of evidence—coaching them to think more deeply and construct stronger, more nuanced responses. This constant practice and targeted feedback builds the analytical muscle they need to excel on exam day.

Can Magna save me grading time while still assessing complex skills?

Absolutely. Grading hundreds of complex AP-style essays is one of the biggest time sinks for teachers. Magna automates this process, providing instant, rubric-aligned feedback on every student submission. This frees you from spending nights and weekends with a red pen and gives you back valuable time to focus on lesson planning, small-group instruction, and targeted interventions. You get deep insight into student thinking without the grading burnout.

Will my students get better AP scores using Magna?

The data speaks for itself. Magna students have 3X higher odds of scoring a 5 and 2X higher odds of scoring a 4+ on their AP exams. By providing unlimited, high-quality practice with AI-driven coaching, Magna helps students master the difficult analytical components of the exams that often separate a good score from a great one. The platform turns practice into measurable progress, building both the skills and the confidence students need to achieve top scores.

How does Magna support different AP subjects?

Critical thinking isn’t one-size-fits-all, and neither is Magna. The platform offers tailored content and feedback for over 11 AP subjects. An AP U.S. History student receives feedback on their ability to analyze primary source documents and build a historical argument, while an AP Biology student gets coaching on interpreting experimental data and forming a scientific claim. The AI understands the unique demands of each subject, ensuring students practice the specific thinking skills they’ll need for their exam.

Ready to see how AI can help you teach and assess critical thinking more effectively? Magna Education gives teachers the tools to slash grading time, provide instant, meaningful feedback, and get the data they need to drive student success.

Discover a smarter way to prepare your students for their AP exams.