Struggling to remember whether DNA has deoxyribose or if RNA uses uracil? You’re not alone. For many AP Biology students, who want to master AP Biology, the subtle but key differences between DNA and RNA are a major source of confusion, leading to lost points on exams. What if you could finally master these concepts and turn a common stumbling block into a source of confidence? At Magna Education, we’ve helped thousands of students achieve their goals, with 88% of our students (who reported their AP scores) scoring a 4 or 5 on their AP exams. Our AI-powered platform is designed to clarify complex topics just like this one, providing the targeted practice you need to excel. This guide will break down the essential distinctions between these two vital molecules, giving you a clear, exam-ready understanding of how life’s genetic code is stored and put into action.

Understanding the Genetic Blueprint

Every living thing, from a single-celled bacterium to a blue whale, runs on a genetic operating system. At the core of this system are two molecules: Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA) and Ribonucleic Acid (RNA). Though they work in tandem, their jobs are distinct, and it all comes down to their molecular design.

DNA is built for the long haul. Its job is to be the stable, secure archive of an organism’s entire genetic code. That iconic double-helix structure isn’t just for show; it shields the precious genetic information inside and provides a beautifully simple way to make copies. This durability is non-negotiable for passing accurate information from one generation to the next.

RNA is the dynamic, on-the-go messenger. It’s created from a DNA template when a specific instruction is needed—a process called transcription. RNA then carries that instruction out of the cell’s nucleus and into the cellular machinery that builds proteins. Because its role is temporary, RNA is designed to be more reactive and less stable, letting the cell turn genes on and off as needed.

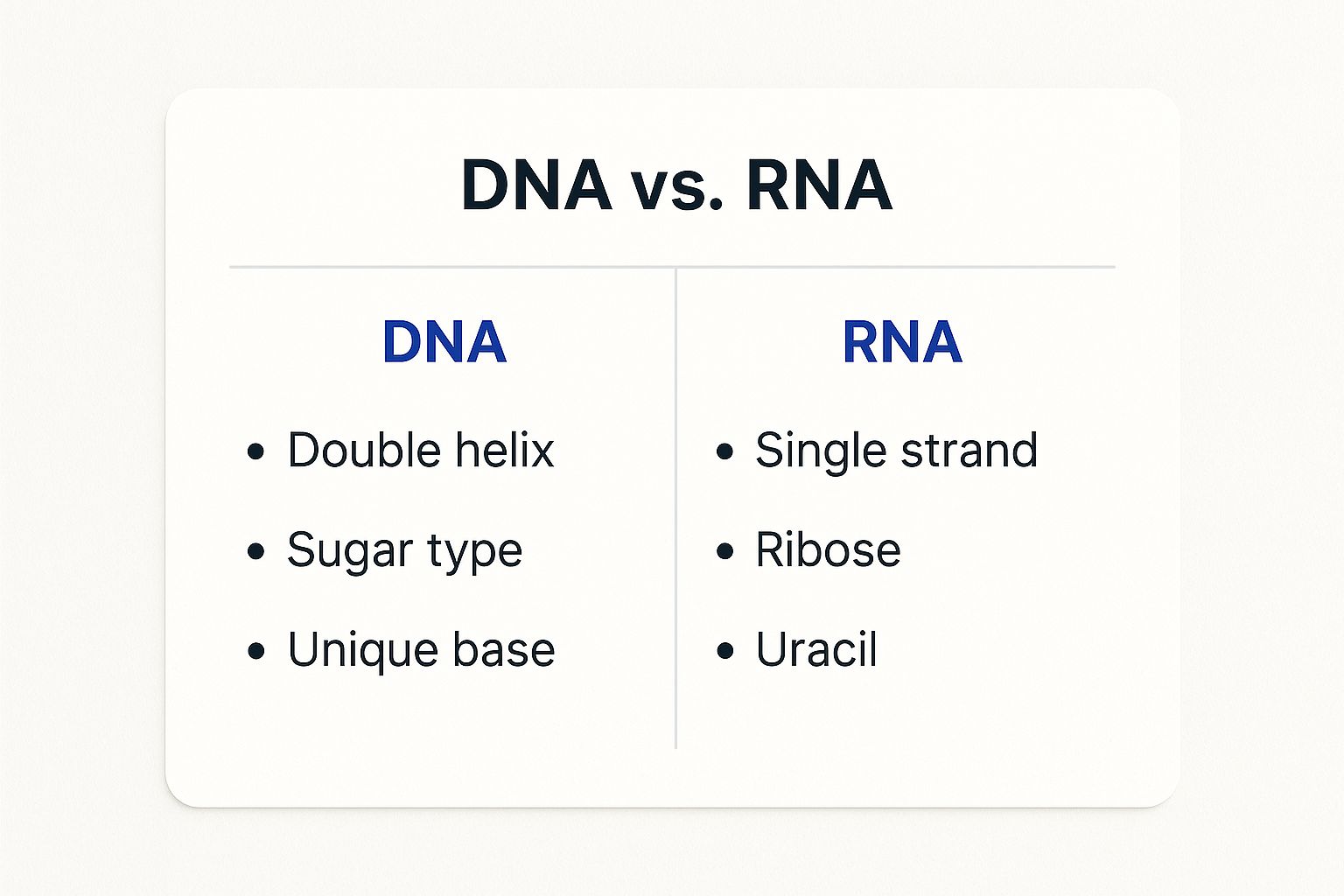

This infographic breaks down the most critical distinctions at a glance.

As the visual shows, everything about DNA—its double helix, deoxyribose sugar, and use of thymine—is optimized for stability. In contrast, RNA’s single strand, ribose sugar, and use of uracil make it the perfect molecule for its active, short-term assignments.

DNA vs RNA Quick Comparison Chart

To really nail down the differences, a side-by-side look can be incredibly helpful. Think of this table as a cheat sheet for the five most important distinctions between these two nucleic acids. It sets the stage for the deeper dive we’re about to take.

| Feature | DNA (Deoxyribonucleic Acid) | RNA (Ribonucleic Acid) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Long-term storage of genetic information; the master blueprint. | Transfers genetic code from the nucleus to ribosomes to make proteins; a “working copy.” |

| Structure | A double-stranded helix with a uniform, stable structure. | A single-stranded molecule that often folds into complex 3D shapes. |

| Sugar Component | Deoxyribose sugar. | Ribose sugar (it has one extra oxygen atom). |

| Nitrogenous Bases | Adenine (A), Guanine (G), Cytosine (C), and Thymine (T). | Adenine (A), Guanine (G), Cytosine (C), and Uracil (U). |

| Stability | Highly stable and resistant to breaking down, perfect for archival storage. | Much less stable and more reactive, making it ideal for short-term tasks. |

With these core differences in mind, we can now explore exactly why these molecules are built the way they are and how their unique properties dictate their roles in the cell.

Comparing the Structural Building Blocks

To really get a feel for the differences between DNA and RNA, you have to zoom in on their fundamental parts. Think of them like buildings: both are made from similar materials—a sugar, a phosphate group, and a nitrogenous base—but the specific type of each component changes the final structure and what it’s used for.

This trio combines to form a single unit called a nucleotide. Millions of these nucleotides then link up, creating the long chains we know as DNA and RNA. But the identity of just one of these parts—the sugar—completely changes the molecule’s personality.

The Critical Role of the Sugar Backbone

At the heart of it all is the sugar. This isn’t just some minor detail; it’s the very reason DNA is a stable, long-term archive while RNA is more of a short-lived messenger. It all comes down to one tiny oxygen atom.

DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) features a sugar called deoxyribose, which is missing an oxygen atom at a specific spot (the 2′ carbon). RNA (ribonucleic acid), on the other hand, contains ribose, which has a hydroxyl (-OH) group right there. That little -OH group makes RNA much more reactive and chemically unstable compared to DNA.

This instability is actually a feature, not a bug. It allows RNA to serve its purpose as a temporary message (mRNA), a delivery molecule (tRNA), or even a biological catalyst (ribozyme), ensuring it can be quickly broken down and regulated by the cell.

This single oxygen atom is a game-changer. Its presence in RNA’s ribose sugar invites enzymes to break the molecule down, ensuring RNA messages don’t linger in the cell longer than needed. DNA’s lack of this oxygen atom makes it far more durable.

The Language of Bases: A, T, C, G, and U

The “letters” of the genetic code are its nitrogenous bases. DNA and RNA share three of them: Adenine (A), Guanine (G), and Cytosine (C). The fourth base, however, is where they diverge, and this switch has huge implications for how genetic information is stored and read.

- DNA uses Thymine (T): In DNA’s double helix, Adenine always pairs with Thymine (A-T). This specific pairing is a key to the helix’s structural stability.

- RNA uses Uracil (U): RNA swaps out Thymine for a similar base called Uracil. Here, Adenine pairs with Uracil (A-U) instead.

This might seem like a small substitution, but it perfectly aligns with their different jobs. Thymine is more energetically “expensive” for a cell to make, but its structure allows for superior proofreading and repair—absolutely essential for a permanent genetic blueprint. For RNA’s fleeting messages, the less costly Uracil gets the job done just fine.

Understanding these subtle yet profound differences is a core part of our AP Biology course.

Why DNA Stores Information and RNA Takes Action

When you get down to it, the fundamental difference between DNA and RNA isn’t just a simple checklist of features—it’s a story of stability versus reactivity. These two molecules were built for completely different jobs. One is designed to protect genetic information for generations, and the other is meant to carry out immediate orders. It all boils down to how their structures are built to handle the chaotic environment inside a cell.

DNA’s entire design is centered around preservation. Its iconic double-helix structure is like a suit of armor, tucking the fragile nitrogenous bases safely on the inside. Combine that with its deoxyribose sugar, and you get a molecule that’s exceptionally stable and not very prone to breaking down on its own. It’s built to last, which is exactly what you need for your master genetic blueprint.

RNA, on the other hand, is built for action and a short lifespan. Its single-stranded nature and the extra, reactive hydroxyl group on its ribose sugar make it chemically fragile. This isn’t a design flaw; it’s a feature that gives the cell incredible control.

Instability as a Feature, Not a Flaw

Why would being unstable ever be a good thing? For RNA, instability means its messages don’t stick around forever. This allows a cell to react quickly to changing conditions—it can produce a specific RNA molecule, use it to make a protein, and then break it down almost immediately. This is crucial for preventing the cell from wasting energy by continuously making a protein it no longer needs.

A perfect example of this is messenger RNA (mRNA), which often has a very short half-life. In bacteria, some mRNA molecules last only a few minutes. This rapid turnover is key to making sure gene expression is a tightly controlled process.

RNA’s inherent instability is the secret to its success. It enables dynamic control over gene expression, letting cells turn protein production on and off like a light switch to adapt on the fly.

How Their Chemistry Shapes Their Roles

These molecular differences have huge real-world consequences, especially in how each molecule interacts with its environment and deals with damage.

- DNA is Built for Reliability: Its stable, double-stranded form makes it the perfect medium for storing information with high fidelity. The structure also makes it easy for the cell’s proofreading and repair machinery to work, minimizing the risk of mutations being passed down.

- RNA is Built for Flexibility: Since it’s a single strand, RNA can fold into all sorts of complex 3D shapes. This allows it to do a lot more than just carry messages. It can be a structural component (rRNA) or even act as a biological catalyst, like an enzyme (ribozyme). Its reactive nature is perfect for these diverse, short-term gigs.

Ultimately, you can think of DNA as the secure, unchanging library that holds the master plans. RNA is the disposable, versatile memo sent to the factory floor, making sure the right instructions are followed at exactly the right time before being discarded.

Comparing Helical Shapes and Structures

While the double-strand versus single-strand distinction is a big one, the differences between DNA and RNA get even more interesting when you look at their 3D shapes. The specific geometry of these molecules is no small detail—it directly controls how they plug into the cellular machinery that reads and acts on genetic information.

DNA almost always twists into what’s called the B-form helix. This is the classic, graceful spiral you see in every biology textbook. It’s a right-handed helix that’s fairly long and slender, which creates obvious major and minor grooves along its surface. These grooves are critical; they act as perfect docking sites for proteins that need to “read” the DNA sequence.

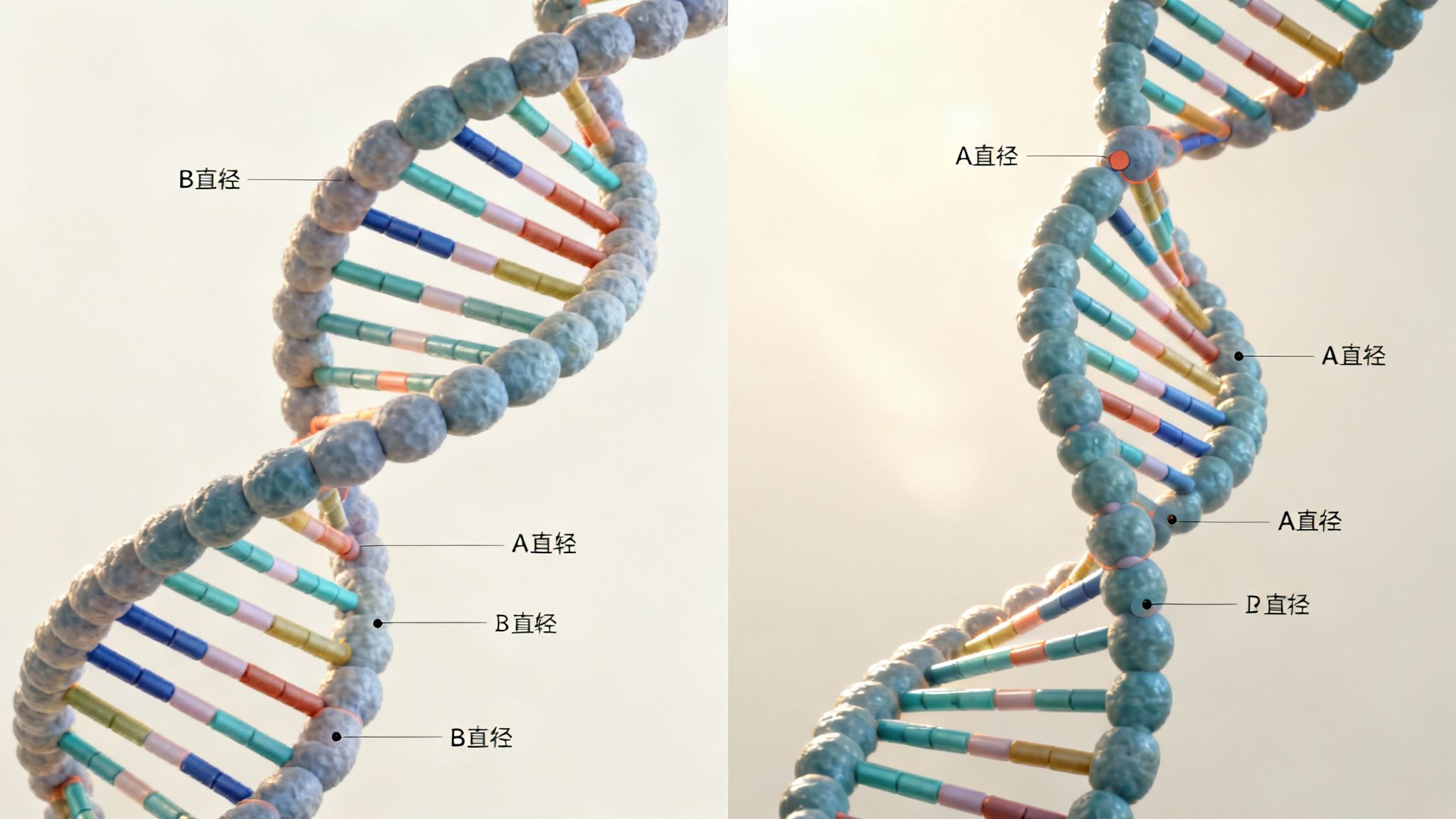

A Tale of Two Helices: The B-Form vs. The A-Form

Even though RNA is single-stranded, it doesn’t just float around like a string. It often folds back on itself to create short, double-stranded segments. When this happens, however, it doesn’t adopt DNA’s B-form. Instead, it snaps into an A-form helix. This structure is also right-handed, but it’s noticeably wider and more compressed than its DNA cousin.

This structural shift isn’t just a fun fact; it fundamentally changes their jobs in the cell. Under typical conditions, DNA’s B-form helix measures about 20 Å in diameter and makes a full turn every 10.5 base pairs. In contrast, RNA’s A-form helix is wider at roughly 23 Å and is wound more tightly, fitting about 11 base pairs into each turn.

Think of a nucleic acid’s helix as a unique molecular “landscape.” The wide, shallow minor groove of RNA’s A-form presents a completely different binding surface for proteins compared to the narrower, deeper minor groove of DNA’s B-form.

These differences in shape are absolutely essential for processes like transcription and translation. The enzymes and proteins involved are highly specialized, designed to recognize and bind to one specific shape over the other.

- DNA’s B-form is perfectly optimized for stable, long-term information storage while still allowing easy access for DNA-specific enzymes.

- RNA’s A-form, found in its double-stranded sections, is vital for its many roles, from forming the structural core of ribosomes to interacting with RNA-specific proteins.

Getting a handle on these advanced structural concepts is key to a deeper appreciation of molecular biology. The principles of molecular shape and interaction are also core topics you can explore in an advanced AP Chemistry course, showing how function follows form, right down to the atomic level.

Exploring the Functional Roles in the Cell

Beyond just their structure, the biggest difference between DNA and RNA is what they actually do. If DNA is the master blueprint safely locked away in the architect’s office, RNA is the busy crew on the job site—the couriers, contractors, and factory workers turning those plans into a finished building.

Each molecule has a completely distinct set of responsibilities, and the whole operation depends on them working together.

DNA essentially has one massive job: long-term information storage. It acts as the secure, permanent genetic archive for the entire organism. Every single instruction for growth, function, and development is meticulously coded into its double helix and protected inside the cell’s nucleus. Its role is mostly passive, but it’s absolutely critical—it has to preserve this information perfectly and pass it on without errors during cell division.

RNA: The Cell’s Active Workforce

While DNA is the library, RNA is the one doing the work. It’s the reader, the messenger, and the builder all in one. Because it’s single-stranded and more flexible, RNA can twist into different forms, each with a specialized job in carrying out DNA’s instructions. Three main types are the key players in protein synthesis, the process of turning genetic code into the machinery that makes a cell run.

These RNA types work in a beautifully coordinated system to build proteins:

- Messenger RNA (mRNA) is the genetic courier. It’s a direct copy of a single gene from the DNA, made during a process called transcription. This mRNA strand then carries the protein-building instructions out of the nucleus to the ribosomes.

- Transfer RNA (tRNA) is like a molecular delivery truck. Its job is to read the mRNA’s message and go grab the specific amino acids—the building blocks of proteins—that are needed.

- Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) is the factory itself. It’s the main component of ribosomes, and it helps form the bonds that link amino acids together in the right sequence, effectively translating the mRNA’s message into a brand-new protein.

RNA’s functional diversity is its greatest strength. While DNA is a static blueprint, RNA is a dynamic workforce with specialized roles—a messenger (mRNA), a transporter (tRNA), and a manufacturer (rRNA)—all working together to execute genetic commands.

To give a clearer picture, here’s a breakdown of what each key molecule does.

Key Functions of DNA and Major RNA Types

| Molecule Type | Primary Function | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|

| DNA | Stores the complete genetic blueprint for an organism. | Double-helix structure ensures stability and protects genetic information. |

| mRNA | Carries a copy of a gene’s instructions from the nucleus to the ribosome. | A temporary, single-stranded copy of a gene; its sequence dictates the protein structure. |

| tRNA | Delivers the correct amino acids to the ribosome during protein synthesis. | “Cloverleaf” shape with a specific anticodon to match the mRNA codon. |

| rRNA | Forms the structural and catalytic core of ribosomes, the protein-making machinery. | Combines with proteins to form ribosomes; catalyzes the formation of peptide bonds. |

This table highlights the core division of labor: DNA holds the master plan, while the various RNA molecules handle the active execution.

But it doesn’t stop there. Scientists have also found a whole class of regulatory RNAs, like microRNAs (miRNAs) and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), that act like project managers. They can fine-tune which genes get expressed by blocking mRNA from being translated. This adds yet another layer of control, showing that the differences between DNA and RNA go far beyond their basic structure. RNA is an active, multi-talented manager of the cell’s day-to-day business.

How RNA Differs From Its DNA Template

It’s easy to think of RNA as a perfect, one-to-one copy of a DNA gene, but the reality is far more dynamic. The process of transcription isn’t always a flawless dictation. In fact, an RNA strand can sometimes differ from its DNA template from the very moment it’s created, introducing a fascinating layer of variation into the genetic message.

This phenomenon adds another critical point to the differences between DNA and RNA, showing that the cell treats its permanent genetic record differently from its temporary, working instructions. The RNA message itself can be modified almost immediately, creating a flexible, adaptable script.

Introducing RNA-DNA Sequence Differences

These variations are known as RNA-DNA sequence differences (RDDs). They represent a sophisticated level of biological regulation where the RNA sequence doesn’t perfectly match the DNA segment it was transcribed from. This isn’t just a rare anomaly; it’s a recognized mechanism for creating diversity in the messages sent to the protein-making machinery.

In human cells, researchers have identified all 12 possible types of RNA-DNA nucleotide substitutions occurring in newly made RNA strands. For a variation to be considered a significant RDD, at least 10% of the RNA produced from a specific gene must show a sequence that diverges from the original DNA code.

The early appearance of these RDDs suggests they aren’t caused by the usual RNA editing mechanisms, which typically happen after transcription is complete. To learn more, you can explore the findings on RNA-DNA differences.

This early-stage variation challenges the textbook model of transcription. It suggests that the cell has mechanisms to introduce changes as RNA is being synthesized, allowing for a rapid and flexible way to alter genetic output without touching the original DNA blueprint.

The existence of RDDs highlights a fundamental principle: DNA is the stable, unchanging archive, while RNA is a flexible and adaptable script. By allowing for these immediate variations, cells can generate a wider range of proteins or regulatory molecules from a single gene. This provides a powerful tool for adapting to new conditions without altering the core genetic code.

Ultimately, this distinction underscores RNA’s role not just as a messenger, but as an active participant in managing genetic information.

Common Questions About DNA and RNA

Even after a side-by-side comparison, some questions about DNA and RNA still pop up. Let’s tackle the most common points of confusion to really lock in your understanding of these crucial molecules.

Why Does RNA Use Uracil Instead of Thymine?

The swap from thymine (T) in DNA to uracil (U) in RNA might seem random, but it’s actually a brilliant bit of molecular engineering for error-checking and saving energy.

Cytosine (C), one of the main DNA bases, has a pesky habit of degrading into uracil. Because DNA’s code is meant to last a lifetime, the cell needs a way to spot these errors. By using thymine as the standard, any uracil that shows up in DNA is immediately flagged by repair enzymes as damage and fixed.

RNA, on the other hand, is a temporary message. The cell doesn’t need to invest in the same level of high-fidelity proofreading for a molecule that will be broken down quickly anyway. Using uracil is also less energy-intensive for the cell, making it a practical choice for short-term tasks.

Think of it this way: thymine is the cell’s built-in defense against mutation. By making uracil an “illegal” base in the genetic blueprint, the cell can easily spot and repair one of the most common forms of DNA damage.

Can DNA Be Single Stranded or RNA Double Stranded?

Absolutely, though these aren’t their typical forms. For instance, some viruses have genomes made of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA). Their entire survival strategy revolves around hijacking a host cell’s machinery to create the second strand and replicate.

On the flip side, while we think of RNA as single-stranded, it often folds back on itself. This creates intricate 3D shapes with short, double-stranded regions. These areas are vital for the function of molecules like tRNA (transfer RNA) and rRNA (ribosomal RNA) and form what’s known as an A-form helix—structurally quite different from DNA’s classic B-form helix.

What Is the Single Most Important Difference?

If you have to boil it down to one thing, it’s the sugar in their backbones. It’s the foundation for almost everything else.

DNA’s deoxyribose sugar gives it incredible chemical stability, which is exactly what you want for long-term genetic storage. In contrast, RNA’s ribose sugar has an extra hydroxyl group that makes the molecule more reactive and much less stable.

This one chemical difference is the root cause of their distinct structures, functions, and lifespans inside the cell. For any other tough molecular biology questions, you can always ask our AI-powered tutor for instant help.

Mastering the differences between DNA and RNA is crucial for AP exam success. Magna Education empowers students and teachers with AI-driven tools that generate, deliver, and grade AP-style assessments in seconds. Our platform offers personalized study plans and actionable feedback, helping students improve their odds of scoring a 4 or 5. Discover how we can help you achieve your AP goals at https://magnaeducation.ai.

AP is a registered trademark of College Board.